|

Dedication: Saint Elian Location: Llanelian Coordinates: 53.27698N, -3.71008W Grid reference: SH860769 Heritage designation: none |

HOME - WALES - DENBIGHSHIRE

|

Dedication: Saint Elian Location: Llanelian Coordinates: 53.27698N, -3.71008W Grid reference: SH860769 Heritage designation: none |

Saint Elian was unusual in the fact that he was of the 5th century, unlike the majority of Welsh saints, who were active a hundred or so years later. According to tradition, Elian sailed to Wales from Rome, landing on the coast of Anglesey, where he established a church at Llaneilian (which boasts another of his holy wells). He seems to have ventured inland too, and undoubtedly founded Llanelian's church; his Anglicised equivalent is St Hilary, to whom this church is now dedicated. Elian's medieval cult was certainly strong in these two parishes, although it does not seem to have spread further afield.

The earliest reference that I have found to Ffynnon Elian dates from 1699, and can be found in Edward Lhuyd's Parochialia. It would appear that the well's reputation for healing sick children had survived the Reformation almost completely intact, and, unusually, the medieval ritual that was required to effect a cure was still being performed (in most cases, healing rituals were known of but no longer performed by this time). Lhuyd mentioned "Ffynnon Elian ymhlwy Lhan Drilho" ("Elian's Well near Llandrillo") twice, first to note that "a Phapistiad a hên bobl ereilh a offrymma yno rottie gynt, ag etto nailh ai grottie ai i gwerth o Vara" ("Papists and other elderly people used to offer groats there in the past, and still others offer their groats or their value in bread"), and secondly to describe the ritual. Of this, he said "arverynt dhwedyd mae'n rhaid y chwi dhyspydhy'r Ffynnon dair gwaith dros vy mhlentyn mae yn glâv: a chwedi hynny offrwm Grôt", which Lhuyd translated himself as "they are used to say you must throw out all the water out of the well 3 times for my sick child & then offer ye groat".

This medieval tradition was soon to take a back foot, however, as the next century saw the transformation of this relatively ordinary holy spring into a so-called "cursing well". It looks as though this began in the late 18th century, and it appears to have been the brainchild of a particular Mrs Holland, on whose land Ffynnon Elian was located. She lived with her husband, Jeffrey Holland, who was both a magistrate and the rector of two Welsh parishes, on Cefn y Ffynnon Farm. It is unclear whether Mrs Holland invented the concept of cursing herself, or whether she took advantage of a small localised tradition that was already extant, but the former is much more likely. Either way, she was clearly very enterprising, and it is rumoured that she earnt as much as £300 (equivalent to around £35,000 today) annually from her occupation as "priestess" of the well.

All of Ffynnon Elian's custodians, or "priests", as they were commonly known, had slightly different methods of effecting and removing curses. Under Mrs Holland, the names of those cursed appear to have been inscribed on pieces of slate, which were kept at the well (some sources indicate that they were locked within a nearby chamber that was filled with the well's water), and entered into a book held by Mrs Holland at Cefn y Ffynnon. When a person wished to have their name "taken out of the well", the slate would be removed, and their entry in Mrs Holland's book erased. Both services would only be performed for a not inconsiderable fee. The locked chamber in which these slates were kept was seen by Mark Luke Louis, who was touring Wales at the time, and who published details of his travels in 1824 in Gleanings of a Tour in North Wales; he described it as "a second well" behind "a little [locked] door", behind which, he was informed, were "a number of pieces of stone, on which are written the names of those unfortunate beings who are offered up to his infernal majesty".

As custodian of such a place, Mrs Holland naturally obtained an undesirable reputation. A piece on Ffynnon Elian that appeared in the Manchester Iris on the 9th of August, 1823 (by which time Mrs Holland had been succeeded by the next "priest"), described her as "the Cursing Hag of the well", and Owen Owen Roberts, writing in 1847 in Education in North Wales, described her as the "superintending Pythoness in the orgies of witchcraft at Ffynon [sic] Elian".

Regardless of her own reputation, Mrs Holland was responsible for the increase in popularity and fame that the well saw in the late 1700s. As early as 1775, "a fellow (who imagined I had injured him)" threatened Thomas Pennant, who was touring North Wales at the time, that he would "curſe me with effect" at Ffynnon Elian. Pennant described several ways in which the well was then used, notably for "the cures of all diſeaſes", "diſcovering thieves" (and "recovering ſtolen goods"), and "to requeſt the ſaint to afflict with ſudden death" people's enemies. Clearly the site's fame only grew in the next decade, however, as, in 1796, Pennant described the unusual plight of local "turnep" farmers in his History of Whiteford and Holywell (it is said that whole farms were often cursed at the well):

|

Beyond the ſpace between the boundary and the mountain is a tract of light ſoil, which may be ſaid to begin under Kelyn, in the townſhip of Uchlan, and continue in a direct line by Tyddin Ycha, to Plas Ycha, in the townſhip of Moſtyn. This is extremely well adapted for that uſeful root the turnep [sic]; and it has been tried with ſucceſs. But the farmer is obliged to give up the cultivation, by reaſon of the depredations the poor make on the crops. They will ſteal the turneps before his face, laugh at him when he fumes at them; and aſk him, how he can be in ſuch a rage about a few turneps? As a magiſtrate, I never had a complaint made before me againſt a turnep-ſtealer... Incredible as it may appear, numbers of them are in fear of being curſed at St. Ælian's well, and ſuffer the due penalty of their ſuperſtition. |

According to The Manchester Iris, Mrs Holland was later prosecuted for fraud by the "justices of the peace for the county of Denbigh", who also ruled that the well should be "choked up with rubbish". Nevertheless, a new "priest" quickly filled her place. This new custodian was a Mr John Edwards (who was later dubbed "the Welch [sic] Cunjuror"), of Berth Ddu, near Halkyn in Flintshire. Although he did not live in Llanelian, he seems to have been working in league with the landowner, Margaret Pritchard (who was reportedly known as "dynes y ffynnon", or "woman of the well"), and people who wished to use Ffynnon Elian, or to be taken out of it, were sent to his house in Flintshire for further advice. He was certainly active in this role by 1813, although he may have begun his practices earlier. By Edwards' time, the ritual that had to be performed to "take a person out of the well" had become extremely complicated; whether this had developed during Mrs Holland's time or was Edwards' own invention is unclear. William Jones described the rituals that Edwards performed in his Essay on the Character of the Welsh (1841):

|

When the cunjuror had received his fee, he wrote the name of the individual to be cursed, on a little parchment, which he folded up in a piece of thin lead, to which he attached, by a string, a small slate, on which he wrote the initials of the name. The whole was then thrown into the well, by doing which he repeated the curse to be inflicted, taking up, and letting down again, some portion of the water... In a house, in the vicinity, he that had been cursed read, or had read for him, two Psalms; then he walked round the well three times; after which he read again some portion of the Scriptures; then the well was emptied of its water, and the slate, together with the lead inclosing his name, was given to him. When this was done the individual was dismissed, and recommended to read large portions of the book of Job and the Psalms, for the three succeeding Fridays. |

Edwards' reign as "high priest" of Ffynnon Elian did not last, however, and he soon found himself in court. In 1818, at the Flintshire Great Session, he was sentenced to twelve months imprisonment for fraudulently obtaining 14 shillings and 6 pence (equivalent to roughly £40 today) from a man who believed that his name had been put into the well. The prosecutor in this case was a man named Edward Pierce, from Llandyrnog, in Denbighshire, whose testimony, as heard in court, was published in 1819 in The Christian Reformer:

|

I live at Llandyrnog, in the county of Denbigh. I saw John Edwards, at his own house, called Berth ddu, in the parish of Northop, in the month of April, 1813. I understood I had been put in Fynnon [sic] Elian; I mean my name had been put in. I thought something was the matter with me; I saw every thing going cross. I was informed that John Edwards pulled people out of the well; I went to him in order to be pulled out. I told him something was the matter with me. He immediately observed, that my name was put in Fynnon Elian. I trembled! - He said it was not then a fit time to take my name out, but desired me to wait till the next full moon, when he would take me out. He requested me in the interim, to read the following psalms, 6, 7, 20, 68, 109 and 118; afterwards he would let me know when to go to Fynnon Elian, as there were other people to go with us - it was absolutely necessary to go there: I went to his house in May following, to inquire about the proper time to go to the well. He said we would go the following Sunday, and desired me to meet him in St. Asaph. - We met there at seven o'clock on the Sunday evening - it was then full moon! When I saw him at St. Asaph, he desired me to go on one side with him to pay the money, which he said was to be given to the woman of the well [Margaret Pritchard], for taking my name out: he said if I paid him, my name would be taken out. I was to pay 15s. but I told him I had only 14s. 6d. by me, which he accepted! He told me, that in consequence of having my name taken out, I should have my health and authority as I wished to have. I paid him the money in order that my name might be taken out. John Edwards, myself, and two other men, on the same business, then started for the well: we arrived there from twelve to half-past twelve on Sunday night. I never saw the well before: Edwards called me to the well and shewed it me. We went to a stile near the well; he bid us three go over and remain there till he fetched the key from the house where the woman of the well lived. He told me he would then pay the woman, - he did not say where the house was. The well was inside a fence. I did not see a key; there was no door on it to my knowledge. Edwards was absent about ten minutes; when he returned, he desired one of the men to follow him. One of the strangers went with him; when the man returned, I went in his stead. I found Edwards at the well: he bid me stand on one side of the well, and say the Lord's Prayer. I did so. He then emptied the well with a small wooden cup. When emptying it, he prayed to Father, Son and Holy Ghost; the well then filled again. He put some water into the cup, and desired me to drink some of it, and throw the remainder over my head: he said I must do so three times. I complied. After this, Edwards said, now we will look for your name, he put his hand a little above, near where the water goes into the well; he found something immediately, and said, "here is something," which he gave to me. He desired me to put my hand in; I did so, but could find nothing. What he gave to me was a piece of slate, a cork, a piece of sheet lead, rolled up and tied together with a wire. I did not open it till I got home. It was in my possession till then. When I opened the sheet lead, I found a piece of parchment inside, with the letters E.P. upon it; there were also some crosses. It was too dark to read at the well. When Edwards gave it me he said he thought it was my name, and said every thing would be right and go on well with me, and that I should come on better than usual. I gave the slate, &c. to Mr. Edward Thelwall. I had them in my possession till then. |

The Goleuad Gwynedd, a Welsh Methodist publication, also reported on the case in 1819, and recorded the testimony of Margaret Pritchard, who does not seem to have been completely aware of all of Edwards' activities (although she clearly knew him), but who was present at the trial:

|

Bum yn byw yn Cefn y Ffynnon, y Tyddyn ag y mae Ffynnon Elian arno - ac yr oeddynt yn fy ngalw, "Gwraig y Ffynnon." Yr wyf yn adnabod Iohn Edwards. - Ni welais ef yn Mai diweddaf, nac am dair blynedd cyn hyny. Ni thalodd efe 14 Swllt a 6c. i mi, yn Mai diweddat, na ddo un ddimai. Nid oes yr un clo ar ddrws y Ffynnon. Translation: I used to live in Cefn y Ffynnon, the farm where Ffynnon Elian is located - and they used to call me "The Woman of the Well". I know John Edwards. - I did not see him last May, nor for three years before that. He did not pay me 14 shillings and 6 pence last May, nor did he pay me a single penny. There is no lock on the door of the Well. |

If The Christian Reformer is to be believed, then the case was finished quickly: after only "a few minutes' deliberation", the jury decided that Edwards was guilty, and the judge sentenced him to "twelve calendar months" in the county gaol. Reportedly, the judge was in favour of sentencing Edwards to "transportation", but he was lenient because it was his first offence. Indeed, it is said that the jury's initial response to the case was laughter.

Unlike later well-guardians, Edwards does not appear to have returned to Ffynnon Elian after this incident. It did, however, ruin his reputation, and, when Seren Gomer reported in 1833 on a case involving both Edwards and a man named Mr Hughes, it was noted that "daeth allan yn y dystiolaeth mai yr hawlblaid oedd yr hyglod gonsurwr Cymreig" ("it came out in the evidence that the right party was the Welsh cunjuror") who had recently been imprisoned for twelve months. Unsurprisingly, Edwards then lost to Hughes; reportedly, Edwards' reputation was so bad that this result gave "foddhad heillduol" ("special satisfaction") to the whole court.

It was not only Edwards who suffered from the case brought against him by Edward Pierce: Ffynnon Elian itself seems to have been immediately filled in. Hugh Hughes, writing in Yr Hynafion Cymreig in 1823, said that "dywedir fod y ffynnon hon wedi ei llanw i fynu yn ddiweddar" ("it is said that this well has been filled in recently"), and, according to Early Discipline Illustrated, by Samuel Wilderspin (1832), "the celebrity of St. Elian and his protegé died away". It is clear that the tradition of cursing at Ffynnon Elian only prospered with the encouragement of a dedicated "priest" or "priestess"; without their presence, the tradition was forgotten.

However, the tradition did not stay forgotten for long, because an enterprising trickster named John Evans (later nicknamed "Jac Ffynnon Elian", or simply "Jac") soon seized the opportunity to re-open the well. He took over from John Edwards in around 1820, and kept his position as well-guardian for the next three decades. Despite the fact that Ffynnon Elian was not located on his land, Evans found a way around this by building a house near to the well, and then redirecting the spring (via some pipes and a hole in the hedge) onto his land, thus inadvertently transferring it from Caernarfonshire into Denbighshire. He then filled this "new" Ffynnon Elian with a multitude of pebbles and slates that were engraved with different initials; it is said that whenever Evans heard that a person had fallen ill, he would inform them that their name was in the well, and show them their initials on one of the stones. Indeed, by Evans' time, it seems that the tradition of "putting someone in the well" had almost completely died out, and his business model was solely based around the concept of being "taken out of the well".

During the first few years of Evans' time as "priest", the local Methodists became increasingly agitated by the well's ungodly presence. They had certainly been aware of its existence since at least 1801, when it was specifically mentioned as an object of idolatry in a set of rules for Welsh Methodists that were agreed upon at Bala in that year. However, it was in the late 1820s that the Methodists of Llanelian began to campaign against the use of the well for cursing. In 1828, the (previously mentioned) Goleuad Gwynedd magazine published a letter sent by Llanelian's congregation denouncing belief in the well's supposed powers, and asserting that its water was no more special than that of any other spring. This clearly did not have the desired effect, as another letter was published in the magazine in the February of 1829 that rallied against the "baganiaid Cymru" ("Welsh pagans") using the spring. In fact, it was in that very month that the Methodists of Llanelian decided to destroy Ffynnon Elian for good, the exact details of which they described in another letter published in the next edition of the magazine, entitled "Llwyr ddiddymiad Ffynon [sic] Elian!" ("The complete abolition of Ffynnon Elian!"); ironically, they stated in this letter that anyone who re-opened the well would surely be cursed:

|

Yn y mis diweddaf, darfu ni fel gwlad, o un galon, gyduno i'w chau i fynu; ac fel y canlyn y gwnaethom: Cloddiasom ffôs ddofu o'i hamgylch, a ffôs arall o ddeutu dwy lâth o ddyfnder, yn myned o'r ffôs gyntaf yn union i'r afon, yr hon sydd o fewn ugain llâth i'r ffynon, yn ngwaelod nant. Rhoddasom y cerig oedd yn fur o'i hamgylch yn ngwaelod y ffosydd i gàrio y ffrwd tan y ddaear i'r afon: a dysgwyliwn y bydd cnwd toreithiog o gloron (potatoes) yn tyfu ar y llanerch yr hâf nesaf! Translation: Last month, as a nation, with one heart, we agreed to close it up; and as follows, we did so: We dug a deep trench around it, and another trench about two feet deep, leading directly from the first trench to the river, which is within twenty yards of the spring, at the bottom of the valley. We placed the stones that formed its wall at the bottom of the trenches to carry the stream underground to the river: and we expect that a bountiful crop of potatoes will grow on the clearing next summer! |

Of course, Evans was not to be defeated that easily, and it seems that the well was back in use almost instantly.

As with John Edwards, Evans soon found himself in trouble. In around 1830, he was taken to court by a woman named Elizabeth Davies, who had previously visited Evans, believing that her husband, Robert Davies, had been "put into Ffynnon Elian"; Evans had charged her seven shillings, worth around £30 today, for his services. According to The Carmarthen Journal, Evans was taken to the Denbighshire Assizes, which were held at Ruthin, for the case to be decided. Samuel Wilderspin recorded the testimony of Elizabeth Davies in Early Discipline Illustrated (1832):

|

I went to him to know if my husband's name were [sic] in the well. He said he would see, and sent a girl out with a man, who soon returned with some pebbles and slates, on which various initials were written or engraved. He looked at them attentively, and said my husband's name was not among them. The girl was sent a second time, and she brought back a dish half full of small pebbles, which were thrown upon the table by the prisoner. I picked out one from among them marked R. D., and asked him if that was meant for my husband. He looked at it, and said, 'Yes.' I said to him, 'Did you put my husband into the well?' He replied, 'No.' I was not satisfied, and told the prisoner I did not think it was my husband's pebble; but he insisted that it was, and the water would prove it. Both of us went to the well, and he bade me drink it, which I did. He then said there was no doubt that the letters on the pebble meant my husband, and that when I returned home, I should find him better, and that ten shillings was the lowest price he could charge for taking my husband out of the well. I said I had not so much money, but would procure it, and return as soon as I could. By his permission, I took the pebble home. He cautioned me not to shew it to any one; and in answer to my inquiry, what I should do with it, he said, I must bruise it, mix it with salt, and thow it into the fire. He said he knew who brought the illness on my husband, and that he could, if he thought fit, put him into the well, and afflict him with any disease or misfortune. I said, 'Pray do no such thing, for I leave it to God to deal with the person who has punished my husband, and caused all my sufferings. |

Wilderspin also recorded the testimony of William Davies, Elizabeth's brother-in-law, who had visited Evans with her:

|

The prisoner took some water out of the well in a leaden vessel, and told me to drink it, and at the same time to thank God and St. Elian for the cure of my brother. I did so; and then agreed to give him seven shillings for a bottle of the water to take home. He ordered me to throw the money into the well, which I did; but the prisoner took it out before it reached the bottom, and put it into his pocket. I then asked him how he knew that the R. D. meant my brother? He said, by the colouring of the water. He then began to discharge the water from the well, and I observed him stir up the mud on one side with his right hand, which rendered the water muddy. There, said he, the water changes colour, to shew you that the pebble taken out means your brother. I asked the prisoner if he knew who had put my brother into the well. He said no, but there was a book in the house that would tell. I went into the house with him; he then put a book on the table and a pack of cards, and asked my sister-in-law if she suspected any one more than another. She said she did. He then told her to whisper who it was into my ear, and when she had done so, he opened a book, and there appeared two circles. My sister cut the cards, and there turned up the three of diamonds; the prisoner then uttered a deal of miraculous words, and at last decided that the person suspected was not guilty. |

Unsurprisingly, Evans was found guilty, and was sentenced to "chwe mis o garchar, a llafur caied" ("six months' imprisonment, and hard labour"), according to Y Gwyliedydd in 1830. It is rumoured that, during his trial (whether this or another one), he claimed that he never charged anyone for his services. The punishments that he received did not deter him at all, and, if anything, the fame of Ffynnon Elian only spread in the following decades. In fact, Evans was taken to court at least twice for his activities. An article entitled Jac Ffynnon Elian, which was published in the Cymru magazine in 1895, gave a reportedly true account of one of the times that Evans was arrested:

|

Daeth cyhuddiad o dwyllo yn erbyn Jac, a chwnstabl sir Ddinbych gariai'r cyhuddiad iddo. Translation: An accusation of cheating came against Jac, and the constable of Denbighshire carried the charge to him. |

Indeed, Evans went straight back to work after he was released from his six months in prison, and, soon after, Angharad Llwyd related in a footnote in his History of the Island of Mona or Anglesey (1833) that he had recently been "in the habit of visiting a poor bed-ridden woman", who had been suffering for some time "under the delusion" that she had been put in Ffynnon Elian. She "speedily recovered her spirits", however, when her husband returned from "taking her name out of the well", at the cost of 2 shillings and 6 pence, worth approximately £10 today.

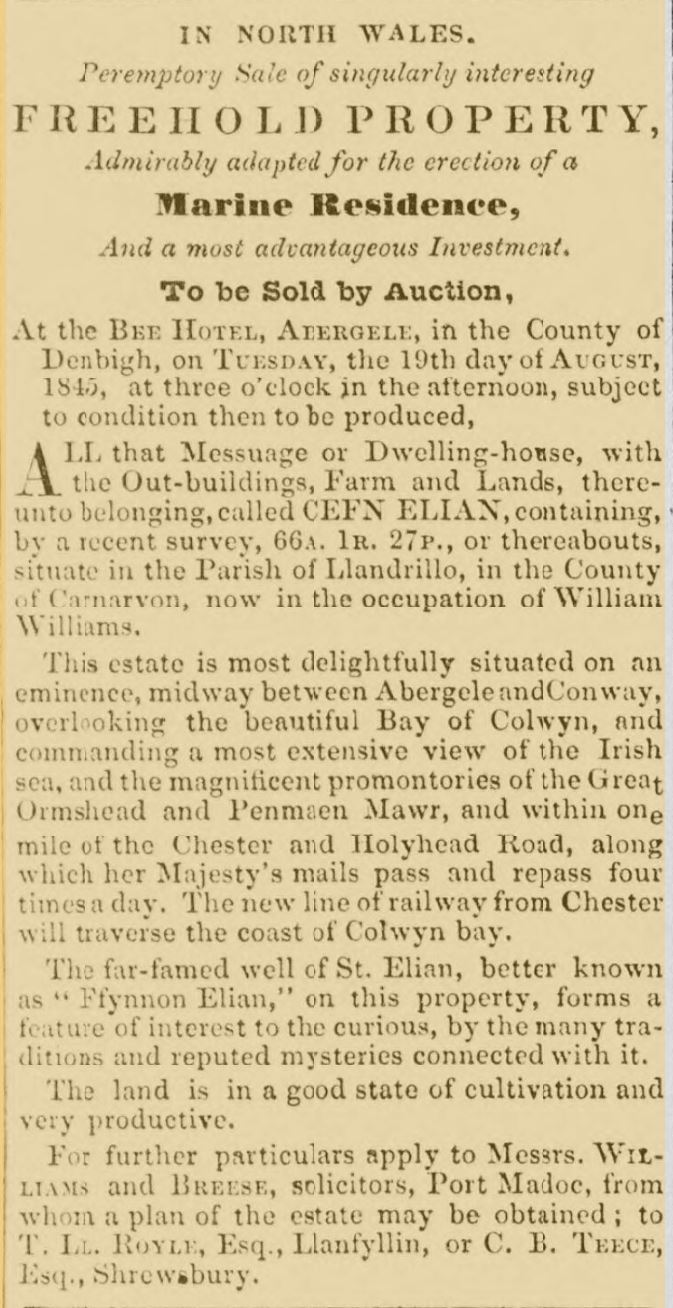

On the 5th of August, 1845, an advertisment appeared in The North Wales Chronicle, publicising the upcoming auction of Cefn Elian (formerly Cefn y Ffynnon), the farm on which the spring that supplied Evans' new well was located. The sale of the farm evidently did not affect Evans' business, however, as Ffynnon Elian retained its fame for the next few years.

|

In 1848, a footnote included in a piece called The Homesteads of Lower Brittany, written by W. Hughes and published in Ainsworth's Magazine, claimed that "it is not unusual at this day" to see people travelling from as far away as "Cheshire and Shropshire to the well of St. Elian", mostly, it seems, for the purpose of cursing their enemies. Locally, Evans' customers appear to have been driven by paranoia, as indicated by two letters that were published in The Gardener's Chronicle in 1849. The first of these was a query sent by an anonymous person who called themselves "E. C.", and who wanted to know why "milk which has calved properly, and appears in every respect as usual, when churned, produce[s] no butter?"; this appeared in the January edition of the magazine. In the next edition, published on the 3rd of February, E. C. had written back with an answer to their own question:

|

It may be satisfactory to the readers of the Gardeners' Chronicle to be informed that "E. C.'s" question concerning the mysterious non-appearance of butter, mentioned in the last number, has been solved, by its being supposed that either the dairymaid or her mistress has had her name put into the "Ffynnon Elian," Anglice - Cursing Well, consequently that the milk was bewitched. The following recipe has been recommended: Put a red-hot poker (if crooked so much the better) into the churn, turning it round three times, at the last turn the witch will feel it, and take her departure. "E. C." has had some difficulty in persuading the dairymaid that this infliction has not proceeded from her having refused to give milk at the door to every one who asked for it, a custom never infringed in Wales without condign punishment, through the intervention of the Cursing Well or witches. At the same time, "E. C." will feel obliged to any correspondent for a more rational cure. |

Yet another example of the paranoia experienced by those who believed in the supposed powers of Ffynnon Elian can be seen in an apparently true story that was told to Elias Owen by "a gentleman", and which he subsequently published in The Montgomeryshire Collections, in an article called Montgomeryshire Folk-Lore (1896):

|

Two men went from Llanidloes to the well on behalf of their sister... These men had reached the neighbourhood of Llanelian, but did not know where the well was nor how to reach it, so they accosted a man they met on the road and asked him where it was. They told him why they had come, and where they came from, and the object of their visit. He informed them that the well was close by, but he advised them to return home at once: that there was nothing in the well, that it was altogether a terrible sham, and a shame that the people were so superstitious. The men, however, intimated that as they had come far they had better proceed to the end of their journey. Seeing that his advice was thrown away upon them, this person directed them how to go to the custodian's abode close by Ffynnon Elian, and taking a short cut reached Jack's house before the strangers could arrive there, and told him of his coming visitors, their errand, and whence they had come. By-and-bye they arrived at Jack's cottage. He told them to sit down, as they must be tired, having walked from Llanidloes. The men looked at each other, evidently surprised at Jack's astounding knowledge, but they were still more so when he revealed to them the business that had brought them to him, and that he had been expecting their visit. Jack told them that he could do all they wished, but that it would cost them five pounds. The men had only four pounds ten shillings between them, and Jack (the well-keeper) told them he would trust them for the balance. These men departed, rejoicing in the success that had attended their undertaking. |

From this account, it appears that the inhabitants of Llanelian were in league with Evans. Indeed, an article (as previously mentioned) published in the Cymru magazine in 1895, entitled Jac Ffynnon Elian, mentioned the surprising fact that Evans was actually well-liked in the immediate locality. According to this article, he was "garedig a hynaws" ("kind and gentle"), so much so that, when he was summoned to court, "cyndyn iawn oedd pob cyfreithiwr i gynorthwyo'r erlynydd" ("all lawyers were very reluctant to assist the prosecutor"). It also claimed that Evans was rarely refused butter or buttermilk when he asked for some at farmhouses; often because the people there liked him, but sometimes because they feared for the "bywyd yr anifeiliaid" ("life of the animals"). Although he was clearly feared by some, it is said that the majority of Llanelian's inhabitants had no belief in the well whatsoever, and instead aided Evans, as they found the whole enterprise amusing.

However, Evans did not maintain his position as "High Priest" of Ffynnon Elian forever. In the last few years of his life, in or around the year 1850, a group of Baptists succeeded in persuading Evans to change his ways, and he soon became a Baptist himself. A letter that he wrote to the Rev. J. Williams, the Baptist minister of Llanddulas, after his so-called "conversion", shows the strength of Evans' feeling:

|

Barchedig Frawd, Translation: Reverend brother,

|

Evans had such a strong desire for his unexpected "repentance" to be widely known that, soon before his death in 1854, he travelled to Llannerchymedd in Anglesey, to beg William Aubrey, the editor of Welsh periodical Y Nofelydd, to publish his "confessions". In 1861, five years after his death, Evans' wish was granted, and his "confessions" were serialised and published by Aubrey as "Hanes Ffynnon Elian", or "the story of Ffynnon Elian" (included in these "confessions" was the above letter). Evans claimed that he had been forced to become the "priest" of the well after so many people had visited him and requested that he "take them out of the well", apparently assuming that he had this power because he lived so close to it; according to him, pretending to "take them out of the well" was the only way that he could get them to leave. He also placed the majority of the blame on gypsies in general, claiming, without clear grounds, that they had begun the tradition of cursing at the well, and that he was thus forced to continue it. This series of "confessions" was so popular that Aubrey proposed to compile them into a book; I have been unable to ascertain whether this materialised.

Without a custodian to fool visitors into paying to either effect or remove a curse, Ffynnon Elian fell almost completely out of use. At some point in the 1860s, a friend of John Rhys, named (coincidentally) Mrs Evans, visited the well and was told, by "an old woman of seventy", that the surrounding bushes had once been "covered with bits of rags" (suggesting that the supposed healing powers of the well were still believed in throughout the spring's time as a cursing well). This Mrs Evans also reportedly saw "corks with pins stuck in them, floating in the well". Intriguingly, the use of corks during the cursing ritual is not mentioned in any accounts of the practice that were performed under the leadership of the well-guardians; perhaps this was a sort of "DIY" version used, after John Evans' death, by people still wishing to curse their fellows.

It does appear that some cursing was still occurring at the well into the 1880s, as, according to an article published in the The Flintshire Observer on the 23rd of July, 1885, the well had been "utterly destroyed a few years ago" by the parish rector. The author of this article, who claimed that they had "frequently heard some one say, I'll put you in Ffynnon Elian!" as a child, had visited the well "a few months ago", to find that "only a puddle remained".

This time, Ffynnon Elian was not immediately re-opened. Despite the fact that it had been destroyed, its site became something of a tourist attraction during the last decades of the 19th century, and it found its way into many tourist guides, including The Gossiping Guide to North Wales (1892), which gave readers directions to the well ("a narrow path through the hedge to our left will take us down some rough steps to what was once so celebrated a well as to be a terror to the Principality"), and described the journey as "another easy excursion". By this point, the site had become popularly known as the "head of the cursing wells".

Ffynnon Elian was still in this state when the Royal Commission, who noted that it "has been filled up", and all that remained was "the old cobbled pathway", visited it on the 20th of June, 1912. Of course, Ffynnon Elian has, historically, never been destroyed for long, and the site was recently restored by its owner, Jane Beckerman. However, when I visited Ffynnon Elian in the May of 2025, I found that it had been abandoned and left to fall into disrepair. The wooden cover that once covered the top of the brick well-head had partially fallen into the spring, and was almost completely rotten, and the path and steps that once provided access to the site had been fenced off with no less than four rows of barbed wire. I could see no inscribed pebbles, slates, or pin-covered corks in the well.

|

Access: The well was once easily accessible from the roadside; although this is clearly subject to change, when I visited, it was possible to glimpse the well through the hedge beside the road. |

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk