|

Dedication: Saint Teath? Location: Llandegla Coordinates: 53.0617N, -3.20296W Grid reference: SJ194522 Heritage designation: none |

HOME - WALES - DENBIGHSHIRE

|

Dedication: Saint Teath? Location: Llandegla Coordinates: 53.0617N, -3.20296W Grid reference: SJ194522 Heritage designation: none |

There is much confusion regarding the true identity of Llandegla's patron saint. For the last few centuries, "Tegla" has been identified with the 2nd century apocryphal companion of St Paul, St Thecla. However, this is undoubtedly incorrect, as St Thecla's cult was not prevalent in Britain at all, and the strength of the cult that existed at Llandegla indicates that Tegla was a local saint. Even prior to the Reformation, Llandegla's patronage was uncertain, with the medieval parish fair being held on the feast day of St Thecla, a Benedictine nun from Wimborne, in Dorset, who never visited Wales and certainly did not travel to Denbighshire.

Llandegla's patron saint is almost certainly the same as that of Llandegley, in Radnorshire (unfortunately, the identity of Llandegley's patron saint has become confused with the 2nd century St Thecla as well). In truth, St Tegla is probably the same as St Teath, also called St Etha, a reputed daughter of the Welsh King Brychan who is said to have founded the village of St Teath, in Cornwall. Indeed, the parish church in St Teath was recorded in 1201 as the church of "St Tecla", suggesting that "Tecla" was an early form of the saint's name. Although there is no record of it, it is not implausible that Teath travelled to Wales at some point during her life and founded the churches of both Llandegley and Llandegla.

Ffynnon Degla itself was reportedly once one of the most popular holy wells in North Wales, and this may be because it was believed to possess such unique healing powers. In 1535, it was recorded that "Offryngs apon Saynt Teglas Dayis troug th eyre [amounted to] viij nobls", worth roughly £1,500 today, showing just how famous Llandegla was in medieval times; it is surely no coincidence that both church and well both once belonged to Valle Crucis Abbey. In particular, the well was thought to have the power to cure epilepsy, and the strength of belief regarding this can be seen in the fact that, locally, epilepsy was called "Clwyf Tegla", or "Tegla's disease"; however, a cure could not be obtained unless the pilgrim partook in a complicated ritual. The exact details of this ritual vary from account to account, but, in essence, the person wishing to be healed would have to walk around the well three times, holding a cockerel, pullet or hen (depending on age and gender) and reciting the Lord's Prayer. Once done, they would circle the church three times, still holding the animal and continuing to recite their Paternoster. The individual would then enter the church, and sleep beneath the altar (the ritual was reportedly always carried out in the evening), wrapped in the church carpet and using the bible as a pillow, still holding the chicken. The following morning, they left the animal in the church, along with an offering of a few pence, and returned home. If the bird died, that meant that the disease had successfully been transferred to the animal, and the person was cured; if the bird showed no signs of having contracted the disease, then the ritual had been performed in vain.

The earliest known exposition of this tradition dates from 1699, and was included in Edward Lhuyd's Parochialia. Lhuyd was informed by the rector of Llandegla of the miraculous cure of John Abraham, a smith in Llangollen, who had partaken in the ritual when he was 13. Lhuyd was told that the ritual was only performed on Fridays, and did not mention the patient having to walk around the well:

|

N.B. Ynghylch Klevyd Tegla ["respecting Tegla's disease"]: one John Abraham a smith now at Lh:Golhen when a Child was troubled wth Klevyd Tegla; on which this Child went 3 times abt ye Church and told ye Lord's Prayer, and afterwards lay him down being in ye edge of night under ye Altar, having the Church bible under his head, and slept there that night. This is always done on Fridays. They give the Clerk a groat at ye Well, and offer another groat in ye Poor's Box. A man has always a cock with him under ye Altar, A woman a hen, a boy a Cockrel & a girl a Pullet. These are given the Clerk, who says yt ye flesh appears black, and that sometimes these Fowls, if ye Party recover, catch ye Disease viz. The falling sickness. 'Tis certain says my author ye Rector, this I. Abr: was by this means perfectly cured & he was then abt 13 y. of age. |

Only eleven years later, Bishop Maddox of St Asaph, in 1710, described the ritual himself. According to him, pilgrims would repeat the ritual around the well, minus the cockerel, after they had deposited the bird in the church the next morning. His is also the earliest mention of the mysterious carved letters that could once be seen at the site:

|

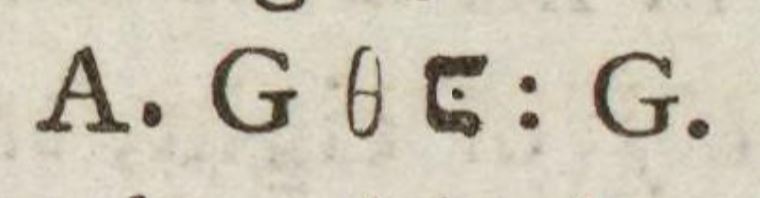

About 240 yds from the Church (about the middle of a quillet of Glebe call'd Gwern Degla) riseth a Well, call'd Tecla's Well, with the following letters cut in Freestone AGEZ:G... In this Well the people that are troubled with convulsion fits or falling sickness call'd St Teccla's evil do use to wash their hands & feet, going abt the well 3 times, saying the Lds prayer thrice, carrying in a handbasket a cock, if a Man; & a hen, if a Woman offering 4 pence in the sd well. All this is done after sunset. Then going to the Ch yd after the same manner go abt the Church, saying the Lds Prayer thrice, getting into the Church sleep under the Communion table with the Church bible under their heads, & the carpet to cover them all night till break of day. Then offering a piece of silver in the poor's box, leaving the Cock or Hen in the Church. They again repair to the Well & p'form as above. -- They say sevl have been heald [sic] yrby (1710). if the cock dyed in the Church, the Patient valaeras [sic] hims. curd [sic]. |

It is thought that this sequence of letters, which has been variously transcribed as "AGEZ:G" and "AGAT:G" (both of these are from two different transcriptions of Bishop Maddox's comments), formed part of a once "monumental" inscription, perhaps in Latin. The only record of the inscription's lettering, excepting that given by Bishop Maddox, can be found in Thomas Pennant's Tour of Wales of 1773, in which a presumably accurate representation of the remaining text was published:

|

It is quite probable that the rest of the inscription had been destroyed during the Reformation, although the medieval ritual clearly survived, very possibly completely unaltered. What is not clear is the exact whereabouts of this inscription on the well's structure; by 1870, the carving had disappeared, and David Richard Thomas, writing in A History of the Diocese of St. Asaph in that same year, reported that he had "failed" to find any trace of it. Perhaps this now lost inscription once held particular significance in the medieval version of the ritual that was performed at the well.

Interestingly, Ffynnon Degla's popularity even after the Reformation was such that no attempts to suppress its usage succeeded in stamping out the custom completely. In 1749, the rural dean "gave strict charge to the parish clerk at his peril to discourage that superstitious practice, and to admit none into the church at night on that errand". Nonetheless, the ritual was still being performed, seemingly regularly, two decades later when Thomas Pennant wrote about the well in his Tour of Wales. In fact, the last known instance of the full ritual being carried out occured in around 1813, when Evan Edwards, the son of the parish sexton, attempted to attain a cure for his epilepsy. Until at least the 1850s, the well's powers were still believed in, but visitors would simply toss coins into the water to effect a cure, instead of performing the proper ritual, as was recorded in a letter in volume 3 of Archaeologia Cambrensis in 1856 that noted that "money is still thrown into the water by persons desirous of recovering from sickness". By 1870, however, Ffynnon Degla's reputation had deteriorated and it became neglected.

By the latter part of the 19th century, the exact details of Ffynnon Degla's ritualistic tradition had become muddled and certain new, probably completely fabricated, elements began to appear in accounts of the custom. Most of these historically incorrect embelishments were introduced to the story by Henry Jenkinson, writing in Jenkinsons's Practical Guide to North Wales in 1878, who claimed that the bird was commonly left by pilgrims "in an old chest" in the church porch, after which it "invariably died"; there is no mention of this idea anywhere before 1878. Jenkinson also asserted that the votary, when beneath the altar, "slept with the beak of the fowl in his or her mouth till break of day", an idea that is not supported by any historical accounts. Additionally, Jenkinson's Guide seems to be the source of the claim that the nearby Berthyrhiniog Well was a part of the Ffynnon Degla ritual, which is very unlikely to be true.

In 1888, a letter published in Bye-Gones stated that the well was in a poor state of repair, it having become "filled up with soil". The parish rector had reportedly planned to restore the site in the summer of 1887, but "the project fell through". When the Royal Commission visited Ffynnon Degla on the 14th of July, 1911, they did not comment on the well's state of repair, although they included it in a short list of "monuments especially worthy of preservation" in Denbighshire. The site was excavated in 1935, and coins and pieces of pottery, along with lots of pins, were discovered in the well. Today, the well has been recently restored with an interpretation board added, and a sign-posted path has been created that leads to it. When I visited in the October of 2024, the site appeared to be in relatively good repair, although the stonework on the southern side looked as though it was in need of some attention, as it was beginning to bulge inwards slightly.

|

Access: The well is located on private land, but the owners have very kindly created a permissive path that leads to it. |

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk