|

Dedication: Saint Chad Location: Stowe Coordinates: 52.689650N, -1.8216092W Grid reference: SK121102 Heritage designation: Grade II listed building |

HOME - ENGLAND - STAFFORDSHIRE

|

Dedication: Saint Chad Location: Stowe Coordinates: 52.689650N, -1.8216092W Grid reference: SK121102 Heritage designation: Grade II listed building |

St Chad, the patron saint of "medicinal springs", has many holy wells, but the one at Lichfield is possibly the most famous of them all. Chad, a 7th century saint who was originally from Northumbria, became the Bishop of Lichfield in 669. Initially, he was sent by the King of Northumbria to the region as a missionary.

St Chad himself is thought to have established a small monastery or cell at Stowe before he became Lichfield's bishop. According to Robert Plot in his Natural History of Stafford-shire (1686), Chad lived a solitary life here, living "only upon the milk of a Doe". Traditionally, it is said that St Ruffin and St Wulfhad (who were both the sons of Wulfhere, the steadfastly pagan king of Mercia) were one day hunting this specific doe, and thus were led by it to St Chad's cell. Chad successfully converted the two pagans, and later baptised them in a well; Plot makes it clear that this well was, in his time, believed to be this very spring, and states that the spring is "yet remaining by the Church of Stow, near the City of Lichfied [sic]". When Wulfhad and Ruffin's father heard about their conversion to Christianity, he became so angered that he had his sons killed (hence their current status as martyrs). Soon after, however, King Wulfhere began to regret his actions and he too converted to Christianity, and ordained Chad the Bishop of Lichfield.

The first known reference to St Chad's Well at Stowe was made in the mid 16th century (the exact date is not known for certain) by John Leland, who appears to have confused Chad with his brother Cedd:

|

Stow-churche [is] in the est end of the towne, whereas is St. Cedd's well, a thinge of pure watar, where is sene a stone in the botom of it, on the whiche some say that Cedde was wont nakyd to stond on in the watar, and pray. At this stone Cedd had his oratorie in the tyme of Wulphere Kynge of the Merchis. |

The particular stone that Leland mentions appears to have been regarded with importance, even after the Reformation. When the well was renovated in the early 19th century, the stone is said to have been built into the wall of the new well-house, although today it has been unfortunately lost. Supposedly it was believed in times past that touching the stone would grant any wish; presumably this custom evolved after the Reformation. The existence of this same stone was also noted in 1608 in The English Martyrologe, which was written by an anonymous "Catholicke Prieſt", who also emphasised the healing virtues of the spring:

|

There is a ſo a VVell neere to the ſame Church [the "Cathedrall"], commonly called S. Chads VVell; In the bottome whereof, lieth, vntill this day, a cleere greate marble ſtone, whereon S. Chad was wont to kneele and pray in his Oratory; the water of which Well, is very wholſome & ſoueraigne for many diſeaſes. |

St Chad's Well was of such importance that it was still believed to have the power to cure certain diseases well into the 18th century. Sir John Floyer of Lichfield, a prominent physician of the time, described the well and its supposed healing powers in 1702 in An Essay to Prove Cold Bathing Safe and Useful:

|

And the Well near Stow, which may bear his Name, was probably his Baptiſtry, it being deep enough for Immerſion, and conveniently ſeated near the Church; and that has the Reputation of curing Sore Eyes, Scabs &c. as moſt Holy Wells in England do, which got that Name from the Baptizing the firſt Chriſtians in them... |

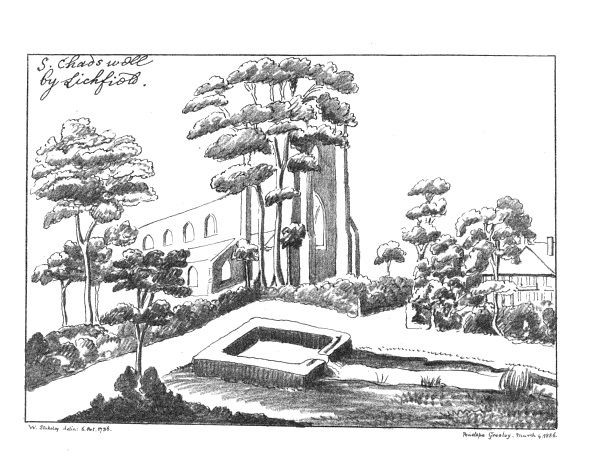

In fact, the well was not forgotten and abandoned after the Reformation, as was the case with most of the country's holy wells. The site was mentioned in numerous publications during the 18th century, including in Daniel Defoe's A Tour Thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain (1748), which described the well as a "spring"; in a letter from Richard Greene, a local antiquarian, to the Gentleman's Magazine on 20th July, 1785, who stated that "many of the Romiſh religion have been known to reſort" to the well, which he called "St. Chadd's"; and by James Bentham in The History and Antiquities of of the Conventual and Cathedral Church of Ely (1771), in which he quoted a comment that had been made by William Stukeley, yet another famed antiquarian, in 1756. The very same William Stukeley drew an image of the well in 1736; it is not known how old the structure was when Stukeley drew it, but it was possibly the very same structure that Leland had described two hundred years earlier.

|

It appears that St Chad's Well became a place for cold bathing (which was effectively a secularised version of the medieval cult of holy wells) during the 18th century. It must have been rather popular, because the very same Sir John Floyer as mentioned above, who was a very strong advocate of cold bathing and plunge pools, built his own rival baths just outside of Lichfield in 1701. He named these baths "St Chad's Baths", and evidently viewed the well at Stowe as a competitor. Floyer must have been confident in his new venture because he took out a ninety-nine year lease of the land that he built the baths on. His Essay to Prove Cold Bathing Safe and Useful, which he first published only a year after he had constructed his baths at Lichfield, acted as more of an advert for his new enterprise than as an essay about the benefits of plunge pools. He made it extremely clear in his "essay" that his baths were significantly colder than the well at Stowe (it seems that it was believed that the colder the water, the better the effects). As if that would not be enough to persuade his readers to visit his baths, Floyer even compiled a list of the ailments that his baths could cure (all of which, he implied, the well at Stowe could not):

|

I have cauſed a Table to be made of thoſe diſeaſes, for which St. Chad's Bathes are proper, with ſome Directions to the Common People. They are good for |

Floyer's baths appear to have been rather successful, although by 1770 the original two baths that he had constructed had been reduced to one bath, and, in the end, St Chad's Well at Stowe outlived Floyer's bathing facilities. Ordnance Survey maps seem to indicate that some remnant of the baths still exist, however, although they have not been used for bathing for at least the last two hundred years.

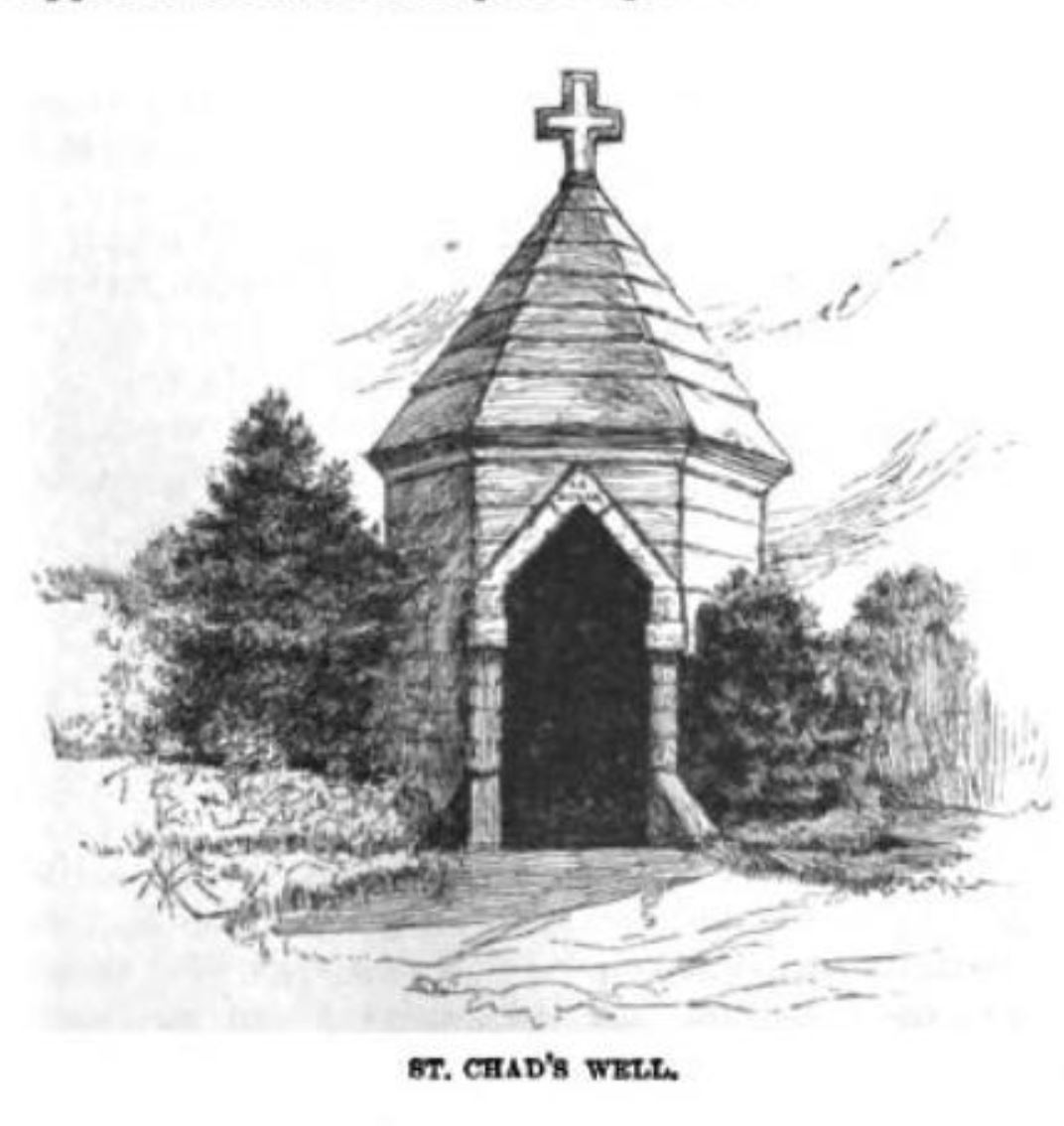

In the 19th century, the well began to fall into a state of disrepair. It was in the 1820s that the well was cleaned out, and an elaborate octagonal well-house (such was its appearance that John Timbs, in 1861, described it as "a small temple" in Something for Everybody) was built over the spring, upon the direction of James Rawson, a local physician who took a particular interest in Lichfield's water supply during the early 19th century. It was Rawson who published, albeit anonymously, An inquiry into the History and Influence of the Lichfield Waters: Intended to shew the necessity of an immediate and final drainage of the pools, in a campaign to have the pools and ponds around Lichfield drained forever because of their filthy condition. In 1864, Rawson wrote about the well and church at Stowe, in a letter entitled "Some Account of St. Chad's Well and Baptistery, Near Lichfield":

|

Whatever the well might have been originally, it had, by the year 1833, degenerated into a most undignified puddle, more than six feet deep: there was not any outlet, as pictured by Stukeley [see the illustration above], for escape of water; the brook was not, as in the drawing, close to the well; and instead of running, as drawn by romance, from W. to E., it ran, as nature drew it, from S. to N. ... At all events, by the date first named here, the well-basin had become filled up with mud and filth; and on the top of this impurity a stone had been placed, which was described by the sight-showers as the identical stone on which St. Chad used to kneel and pray! |

Fortunately, several photographs and drawings exist of the now destroyed octagonal well-house, one of which can be seen in volume 22 of Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly, which was published in 1886, and describes the well thus:

|

But of all the English wells, scarcely excepting Rosamond's, the most notable is that of St. Chad, near Dr. Johnson's town of Lichfield, and at Stowe Church. It remains in some gardens adjoining the west end of that building. The water is sulphurated, and close to it is a pretty iron pump, giving water from a second well, which is superfine chalybeate. At the bottom of the steps leading to St. Chad's Well, and in the middle of the water, is a stone on which, some say, St. Chad was accustomed to stand and pray. |

|

During the 19th century, some superstition was still held regarding the well, as was recorded by R.C. Hope in his Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England (1893), in which he quoted a Rev. Palmer who stated that it was "popularly believed that it is dangerous to drink of the water of St. Chad's Well, as it is sure to give a fit of the 'shakes.'" Well-dressing, which has today been revived and is still carried out at the well, was done at the site in the 19th century, on Holy Thursday.

For whatever reason, the octagonal well-house was allowed to fall into dereliction in the early 20th century. Instead of restoring the Victorian well-house, it was decided that a new structure would be built. Frederick Etchells, an architect and artist who renovated several churches during his career, planned the restoration of the well, and by 1950 the work was complete. It is not known what exactly happened to St Chad's famous stone. It was in the 1990s that the roof of the current structure was covered with a vine.

Today, St Chad's Well can still be seen in the churchyard of St Chad's Church. It is a shame that the octagonal well-house was replaced and not restored; the present construction is rather characterless. At the time of visiting (August 2024), there was a decent depth of clear water in the well, although there was no sign of it being sulphurous, as was stated in Frank Leslie's Popular Monthly.

|

|

|

Access: The well is located in the churchyard of Stowe's church, and is therefore accessible every day. |

Copyright 2025 britishholywells.co.uk